Treblinka

For the overwhelming majority of Warsaw’s wartime Jews their journey was destined to end in one place, a hitherto unknown village called Treblinka. Set 100 kilometres north west of Warsaw this small rural community would find itself unwittingly thrust into the eye of the Holocaust, its name forever etched in mankind’s roll of shame.

Treblinka remains a backwater town, and as such travellers are going struggle to reach it. Put simply, either hire a car and fire up the GPS, or contact one of the Warsaw-based tour companies listed who will be happy to tailor a visit for you. Alternatively, hire a six person minibus for 250zł – call 604 89 63 97 for further details.

Split into two separate sections, Treblinka I and Treblinka II, Treblinka I was originally established in the summer of 1941, and functioned as a Polish slave labour camp. Treblinka II, the death camp, opened the following year, receiving its first human cargo on July 22, 1942. It was designed for the sole purpose of murder, a function it fulfilled well. Measuring 400 by 600 metres, and surrounded with barbed wire fences and watchtowers, the camp was carefully blended into the heavily wooded landscape in an effort to mask its existence. Consisting of a barracks, an armoury and storage areas, the camp also had a fenced off living area housing 1,000 Jews employed to clear bodies, hammer out teeth and shave hair. It was also home to the reception area, where cattle wagons loaded with Jews would screech to a halt. Built to resemble a legitimate train station, it was decorated with clocks, timetables, posters and even an infirmary replete with a Red Cross banner. In actual fact the infirmary was no more than a sinister façade to an execution pit, used to murder prisoners too weak to march to the gas chambers.

Having been stripped naked, arrivals at Treblinka I were then herded up the tube, a fenced off path leading to the ‘shower block’. It was here that prisoners were ushered into gas chambers disguised as bathhouses. Carbon monoxide would then be piped through showerheads, taking as long as half an hour to asphyxiate those locked inside. At the height of the killing process up to 20 railway carriages could be processed within a period of one to two hours. At first bodies were simply buried in mass graves but by 1943, in an attempt to conceal all traces of genocide, corpses were cremated on massive pyres.

Several escape attempts were launched by the permanent staff of Jewish prisoners, with the biggest coming on August 2, 1943. Having obtained a key to the armoury, a core of around 70 prisoners aimed to storm the Nazi barricades, liberate the other prisoners and flee to the forests. The plan was disrupted when an SS officer, Kurt Kuttner, noticed the rebels raiding the munitions store. He was killed on the spot, but the shots alerted the other guards who launched a swift counter-action. In the brief but fierce gun battle that followed many buildings were torched, but only a handful of prisoners succeeded in escaping.

Following the uprising, and a similar one at Sobibor, Himmler took the decision to close down the Aktion Reinhard death camps. By October 4, 1943 Treblinka was levelled, reforested and a family of Ukrainian peasants re-settled on the adjacent farmland. Although it is impossible to place an accurate figure on the number of people slaughtered, conservative estimates suggest that anything from 700,000 to 900,000 people were murdered during the camp's existence. Of the number of Jews who passed through its gates it is thought that fewer than 100 lived to see the end of the war.

Following the war several German and Ukrainian guards were charged with crimes relating to their time at Treblinka. Most escaped with light sentences ranging from three to twelve years. The camp commander, Franz Stangl, fled to Syria and from there to Brazil, until he was finally extradited to face justice in 1970. He died in prison the following year, apparently unrepentant.

What is there to see? Well, not much. The Nazis did a deft job of erasing their crimes, and visitors will require a vivid imagination so as to picture what was. Nevertheless, with some prior knowledge your bumpy journey will be ultimately rewarded; what Treblinka lacks in physical sites it makes up for with sheer skin-prickling menace, and a trip out here is sure to leave you pondering for some time.

Stock up on literature at the car park hut, before making your way to the small exhibition house. Set across two rooms visitors will find a series of items recovered from the site – torah scrolls, cutlery, coins and other keepsakes – as well as a few period photographs illustrating life at the camp. However, the real pull here is the scale model, an intricate work which really brings the grounds to life – details here include a zoo built for the enjoyment of the SS, a Disney style stone tower and the neatly trimmed flower beds past which Jews would have filed on their way to the gas chambers. It’s a fascinating work, and one which provides plenty of pause for thought.

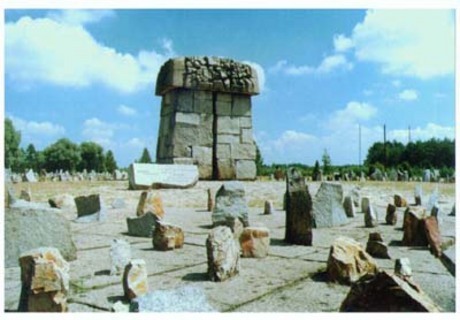

Back outside, a trail of symbolic train tracks show the route trains from Warsaw would have followed before finally terminating at Treblinka platform. For the Jews crammed inside the cattle wagons this represented the last stop in their persecution. Then, directly up ahead, comes the climax of the camp – marking the execution grounds lie hundreds of jagged memorial stones, each one inscribed with the name of a lost community. It’s among these – to the left of your approach – you’ll find the only stone dedicated to a person. That man is Janusz Korczak, a pedagogue and author who famously turned down safe passage from the ghetto in order to stay with the orphaned children entrusted in his care. His most famous work is the children’s tale King Matt the First (Król Maciuś Pierwszy), the adventure story of a young king. As well as telling the story of how the young king deals with the challenges of power in a bygone age, it is also a thinly veiled representation of historical events in Poland and describes many of the social reforms the young king introduces, many targeting children and many of which Korczak himself introduced into his own orphanage. While some of the language might be considered politically incorrect 90 years on it is a fascinating book and one that children today can still enjoy immensely.

Marking the site of the gas chamber stands an overpowering monument designed by Franciszek Duszenki, a message in front of it simply stating: ‘Never Again’. It’s an eerie experience, and the sense of evil palpable. However, there is also more. Unknown to many, a second camp also functioned at Treblinka, a labour camp primarily populated by Poles. Continuing through the route cut through the forest, a stony path leads past a concrete guard bunker before culminating at the vast gravel pit where up to 2,000 Poles were forced into back breaking work. In the field further on, concrete flooring and some foundations mark the outline of former prisoner barracks, while a number of crosses mark what was once the execution grounds. Ultimately haunting, Treblinka is a must see for anyone with a passing interest in modern history – absent are the endless exhibits of Auschwitz, yet even without these this place has a high impact factor which will leave visitors silent.