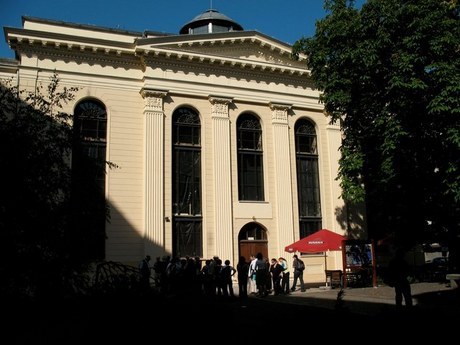

The White Stork Synagogue

The only synagogue in Wrocław to escape the torches of Kristallnacht, the White Stork was built in 1829, taking its name from the inn that once stood in its place. Following the design of prominent German architect Karl Ferdinand Langhans, it is ironically considered a sterling example of 18th century Protestant sacral art. Discreetly hidden from view in a courtyard between ul. Antoniego and ul. Włodkowica, today the surrounding grounds are full of beer gardens, bohemians and graffiti; however it was here that members of the Jewish community were rounded up for deployment to the death camps during WWII. Badly damaged, but not set ablaze (thanks only to its proximity to residential buildings), the synagogue was literally left to rot after the war, before the Jewish community was finally able to recover it from the Polish government in 1996 and initiate restoration. That work is now complete and the synagogue was re-opened in May, 2010. Serving as a worship space and cultural centre, the community’s cultural programme has use of a new multi-functional hall in the synagogue's basement, and there are plans for a museum. Although not yet open to regular visitors, tours can be arranged through the nearby Jewish Information Centre.

Cultural multitude is one of the most important historical and environmental phenomena of Wrocław. While remaining within the borders of many different countries, owning to its location on trade and migration routes, it has become a home for many nations and denominations. The Jews have become one of the most important components that since the very beginning shaped the picture and spirit of the city. The documented history of their presence in Wrocław dates back 800 years but undoubtely it is much older. Their presence, though marked with persecution and exiles, was very beneficial for the city and its development especially economy-wise. The discrimination and isolation, however, did not help the Jews in further joining the cultural and politicaly life of the city. The situation changed when Wroclaw was incorporated into dynamic and modern Prussia. The golden age of the German Jews was about to begin

The end of the 18th century – remembered by the Poles mostly because of the tragic partition of Poland – was time of progress of the Enlightenment in Prussia. One of the most characteristic features was the emancipation of the Jews whose rights were made equal with those of Christians of the Empire. One of its indications was a proposition of erecting a public synagogue, that was put forward in 1790 by the Minister of Silesia, Count Karl Heinrich von Hoy. The temple was to serve the whole Jewish community in the same time allowing the authorities to gain full control over the Jews. It was supposed to replace the houses of prayer scattered all over the city. However, the plan was not accomplished due to lack of interest from the still-dominating group of orthodox Jews. In their view, emancipation was a threat to the religious identity.

Despite the Jewish opposition, the authorities in Berlin continued to pressure. The reluctance, now expanding beyond the conservative Jewish communities was caused both by the lack of funds and the unregulated – despite promises – status of Judaism in the Prussian Constitution. in 1820 the government finally succeded in forcing their decission on the construction of the synagogue. Its completion was set to two years. Between 1819-1820 the large sums of money were gathered and the location of the temple was secured. It was to be erected on the plot on the 35 Sw. Antoni Street where previously the White Stork Inn has been located – hence the name of the temple.

Shortly after that, the architectural plans were ready. Unfortunately, the religious disputes in highly divided Jewish community once again stopped the construction works.

The idea of building a synagogue re-emerged again in 1826 after the initiative of liberal Jews gathered around the First Society of Brothers. The construction works started a year later. The names of the investor – Jakob Philip Silberstein – and the master masons running the construction works – Schindler and Tschoke along with the architectonic supervisor Thiele are etched on the pages of this undertaking. The author of the project – prominent German architect Carl Ferdinand Langhans – has always will be remembered for following the example of sacred Silesian-Prussian -18th Century style of the project. The inside of the temple was decorated by the painter Raphael Biow. The first service took place on the 10th of April 1829 – 13 days before the official ceremonial inauguration.

For the next 18 years the temple was served the function of private synagogue of the Society. Then in 1847 it became the main public synagogue for the growing in size and influence liberal fraction of the local Jewish community.

In 1872 the majestic New Synagogue “Am Anger” was built. Soon the liberal Jews moved to the new temple leaving the old synagogue to the conservatives. The religious requirements of the sex separation forced the construction of three external staircases leading to the women`s galleries. It disturbed the building`s harmonic composition. The later reconstruction of 1905 led by Paul and Richard Erlich resulted in construction of Neo-Romanesque women`s galleries made from reinforced concrete which replaced wooden ones. The biggest and most radical improvement in the synagogue construction took place in 1929 – in the centenary of its existence. During the course of the renovation the exterior and interior of the temple were refurbished, central heating and electric lightning were installed and, at last – in the centre of it bimah was erected.

During the Crystal Night9th/10th of November 1938 the Nazi hit squad devastated the interior of the synagogue. The close proximity to other buildings spared the temple fate of the New Synagogue which was burned to the ground. After temporary quick securing of the building, the temple served for some time as a place of worship for both, conservative and liberal Jews. In 1945 the Nazis converted the synagogue into a garage and a warehouse for stolen Jewish property.

During that time, part of the temple`s original furnishing was destroyed. The courtyard was used as a gathering point for the Jews before their deportation to the death camps. The German Jews of Wroclaw disappeared from the city. They were either murdered or, at best, forced to scatter all over the world. On 13 August 1945 the Jewish Committee in Wroclaw representing the survived Polish Jews asked the City Major – Aleksander Wachniewski – for the return of the synagogue which at that time was occupied by industrial militia. After its recovery, it was renovated and adapted to serve as a place of worship once again.

Despite the waves of Jewish emigration from Poland, the discriminating policy of the authorities and acts of vandalism committed by “unknown individuals” which caused gradual degradation of the building, during the sixties the synagogue served as a temple and a meeting place to the few thousands Jews in Wroclaw. In 1966 under the pretext of extremely bad condition of the building, the authorities ordered its closing.

As a result of the intervention from the Congregation of the Creed of Moses in Wroclaw, a year later, the permission to use lower part of the temple was issued. It was to be used only during some specific holidays. After the demolition of the surrounding buildings, the temple lost its natural protection and became an even easier target for vandals. Constant breaking its windows panes speeded up the process of devastation.

The year 1968 was yet another fatal moment in the history of the Wroclaw Jewish community and its synagogue. The last wave of emigration forced mainly by the anti-Semitic campaign, led to the cancellation of services in the temple.

In 1974 the synagogue was taken over by the government and handed out to the Wroclaw University. The tmple was to be converted into a library and lecture halls of the University Library. The conversion works started in 1976 but were soon abandoned which caused further devastation of the building. After the 1984 acquisition by the Culture and Arts Centre, for a few years the synagogue was used as a venue for artistic performances. The ongoing devastation – mainly due to two fires – led to yet another change of its owners. In 1989 the building was purchased by the University of Music to be converted into a music hall. Unfortunately, shortly after the roof was removed the work stopped and the abandoned temple fell into a state of complete ruin.

The next, since 1992 private, owner didn`t conduct any works – the walls were still dripping with moisture which made the plaster and the decorations to fall off.

Despite the political changes and kindliness of the new, democratic local and central authorities, a couple of years had to pass before the White Stork Synagogue was returned to its rightful owner – the Wroclaw Jews. Much credit has to be given to the Wroclaw metropolitan – Cardinal Henryk Gulbinowicz who convinced the Ministry of Culture and Art to buy the temple and then to give it back to the reborn Jewish Religious Community in Wroclaw on the 10th April 1996.

On September 1995 the first Rosh Hashanah service took place in the ruined synagogue amassing the crowd of 400 people. It was then, when the White Stork Synagogue choir, conducted by Stanislaw Rybarczyk, sung for the first time. May 1996 saw the beginning of the restoration process financed by the Polish-German Cooperation Foundation. The work focused on rebuilding of the roof of the temple and on preparation of plans for further renovation – based on existing archival pictures. In 1998 tehe third stage of the renovation was completed – the cracks in the walls and ceilings were fixed; new windows, parts of the stairs and central heating were installed. The donation from KGHM Polska Miedz S.A. was used to put plaster n some of the walls.

On November 1998 – 60 years after the Crystal Night a special service was held in the synagogue to commemorate the victims of those tragic events. It was a highlight of the struggle for reclaiming and saving the temple – thanks mainly to the efforts of Cief Rabbi of the Polish Republic Michael Schudrich and the leader of the Jewish Religious Community in Wroclaw – Jerzy Kichler. Their work was continued by the successive stewards of the temple – Ignacy Einhorn and Klara Kolodziejska, Karol Lewkowicz and Jozef Kozuch.

In 2005, thanks the donations from the Municipality of Wroclaw, a new floor was laid down and the sorroundings of the synagogue were cleaned and revitalised.

On 7 May 2005 the Wroclaw Centre of Jewish Culture and Education was established and put under charge of Bente Kahan. The distinguished Norwegian and Jewish artist living in Wroclaw since 200, is CJCE President and artistic director of the synagogue. The Bente Kahan Foundation has jojned forces with the wroclaw branch of the Association of the Jewish Religious Communities in Poland in order to renovate the White Stork Synagogue.

Between 2006-2008 the southern façade was reconditioned and the Aron haKodesh restored. Also, the basement was dried and the whole building was made moisture-proof.

In 2007 a consortium of these two institutions – together with the municipality of Wroclaw – was established. The consortium managed by the Bente Kahan Foundation is very effective at acquiring financial means for the complete renovation of the White Stork Synagogue and its courtyard. The restoration works that have begun in 2008 and will last until the end of 2009 will cost about 10 million PLN. This stage of renovation will be financed by the EEA Grants, funds of the non-EU countries, (members of the European Economic Area) won by the consortium in a competition for the projects for the renovation of historic buildings organized by the Polish disposer of the grant (the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage) as well as by the municipality of Wroclaw and the owner – The Association of the Religious Communities in Poland.

The synagogue will keep its ritual functions but it will also strenghten its role as a modern international centre for culture and education including the Jewish Museum that will be established in the basement and on the balconies of the temple. The city will finally regain the Jewish part of its soul.

The White Stork Synagogue is yet again a place of worship – its walls resonate with the sounds of Jewish prayers led by the rabbis Ivan Cane and – since 2006 – Icchak Rapoport.

The Wroclaw Jews gathered here for special occasions and times when the old praying hall is too small to house every member of the community and its guests. The synagogue is also a dynamic centre of Jewish culture – a place of exhibitions, concerts, theatrical performances workshops and meetings. The temple benefits from the great acoustics in its interior as well as from its size – it can accommodate a couple of hundred people.