Odessa Catacombs

Rome has its famous catacombs and so does Paris. But the city with the largest network of underground tunnels is undoubtedly Odessa, Ukraine. Its 2,500 kilometers eclipses the 300 kilometers found in Rome and the 500 kilometers in Paris. Get lost here and you'll be eating rats until you die a dark lonely death.

The catacombs were mostly created during the construction of the city as early engineers mined them for construction material. They were used for various nefarious purposes over the years and as a base for partisans during World War II.

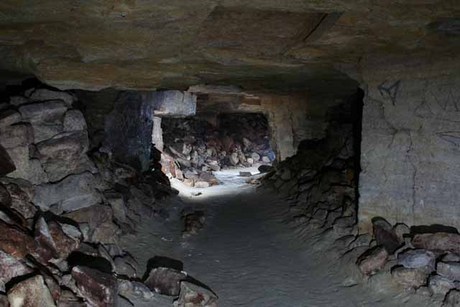

Today, a small portion of the tunnels remain open to the public as a museum dedicated to the partisan efforts. I toured it myself a few years ago and wasn't too wildly impressed. The museum wound through a short section of the tunnels and was strictly average with some random WW II weapons stuffed into cubbyholes and dummies dressed up in partisan costumes. The remaining 2,499 kilometers, however, remain an alluring attraction if you can ditch the tour and find your way in. Bring plenty of bread crumbs to find your way out, however.

The Odessa Catacombs are an estimated 2,500 kilometres of labyrinths stretching out under the city and surrounding region of Odessa, Ukraine. The majority of the catacombs are the result of stone mining.

Most of the city's 19th century houses were built of limestone mined nearby. Abandoned mines were later used and widened by local smugglers. This created a gigantic labyrinth of underground tunnels beneath Odessa, known as the "catacombs".

Today they are a great attraction for extreme tourists, who explore the tunnels despite the dangers involved. Such tours are not officially sanctioned because the catacombs have not been fully mapped and the tunnels themselves are unsafe. There have been incidents of people becoming lost in the tunnel network, and dying of dehydration or rockfalls.

Only one small portion of the catacombs is open to the public, within the "Museum of Partisan Glory" in Nerubayskoye, north of Odessa. The tunnels are often cited as the reason why a subway system has never been built in Odessa.

Most (95-97 %) of the catacombs are former limestone mines, from which stone was extracted to construct the city above. The remaining catacombs (3-5%) are either natural cavities, or were excavated for other purposes such as sewerage.

The first underground stone mines started to appear in the 19th century, while vigorous construction took place in Odessa. They were used as a source of cheap construction materials. Limestone was cut using saws, and mining became so intensive that by the second half of the 19th century, the extensive network of catacombs created many inconveniences to the city.

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, stone mining was banned within the central part of Odessa (inside the Porto-Franko zone, bounded by Old Port Franko and Panteleymonovskaya streets).

During World War II the catacombs served as a hiding places for Soviet partisans, in particular the squad of V.A. Molodtsev. In his work The Waves of The Black Sea, Valentin Kataev described the battle between Soviet partisans against fascist invaders, underneath Odessa and its nearby suburb Usatovo.

In 1961 the "Search" (Poisk) club was created in order to explore the history of partisan movement among the catacombs. Since its creation, it has expanded understanding of the catacombs, and provided information to expand mapping of the tunnels.

Since the beginning of the 21st century limestone mining has continued in the mines located in Dofinovka, Byldynka, and "Fomina balka" near Odessa. As the result of continued mining, the catacombs continue to expand.

Even as far as the Turkish days, Odessa was build over an intricate network of passageways and underground mines tunneled into the spongy rock that served as building material for the city. At one time pirates, later contraband smugglers, had found shelter at these low corridors. Individual foes of the Soviet regime, as well as persons sought as criminals, were said to have taken refuge there in the thirties. Estimated to be over 299 kilometers in length (though much of not high enough to walk through), the catacombs were known to have over 160 exits-some of them leading into cellars of old patrician houses in the city, others into water well, still others into suburban fields and cemeteries. No precise map of the system existed and few dared to go into the catacombs without a trustworthy guide.

It was natural to leave here, in the very heart of enemy’s area, an active underground with supplies, arms, food, and radio communication with Soviet headquarters-close enough to strike out and gather intelligence, yet relatively secure. This plan was particularly appealing as the terrain of most of Transnistria was in no sense suspicious to partisan warfare, being neither swampy not woody (except in the north and northwest). This the Odessa catacombs became the headquarters of the local partisans or more correctly, stay-behind agents; different groups hid there, sometimes unknown to each other; agents who had to disappear from the ‘surface” found refuge there; and at least sporadic contact was maintained between the catacombs and higher headquarters on the Soviet side of the front.

The explosion and tragedies of the catacomb dwellers are the stuff of which drama is made, and it is not surprising that the only realistic account should have been written by a prominent Soviet author; Valentin Kataev, in the form of a novel, on the basis of research on the spot after the war. Although it adhered to the official ethic, Kataev novel proved to be “realistic” that it attracted the ire of the party authorities and was rewritten to order. The first, unrevised edition provides the best available information on the catacombs -in spite of a good deal of “dramatic effect” exaggeration, and the excessive steadfastness and loyalty of his protagonists. His account, due exceptions made, tallies generally with stories from refugees and with what little there is in German and Romanian wartime sources.

The story of the catacomb underground starts shortly before the evacuation of the city. The party oblast committee selected a few men, probably those active in the destruction battalions, to represent the obkom on the spot and to direct small underground groups, one for each rayon of the city and its environs. It is likely that the local NKVD participated in the decision-making, and almost certainly each team included at least one representative or agent of the State Security system.